Requirements

- Students should be familiar with Unity basics

- Intermediate C# programming experience is required

- Design Patterns knowledge is a plus, but not mandatory

Get Udemy’s Dependency Injection in Unity3D using Zenject $10 Coupon, to get Discount on Udemy Course. This Course is a Other Course. This IT & Software Course was instructed by Stepan Diadorov (Test Automation Engineer :: Unity Enthusiast).

Target audience

这篇文章主要为大家详细介绍了Unity实现注册登录模块,文中示例代码介绍的非常详细,具有一定的参考价值,感兴趣的小伙伴们可以参考一下 使用Zenject和UniRx的入门级技术实现了伪登录注册功能。. Download free total video converter old versionunbound.

- Unity developers that want to refactor their existing projects or create new projects using Dependency Injection

- Unity enthusiasts who want to learn the Dependency Injection pattern to use it in the game development.

What Will You Learn?

- 0 813 0.0 C# Dependency Injection Framework for Unity3D. Hence, a higher number means a better unity-sdk alternative or higher similarity. Posts where unity-sdk has been mentioned. We have used some of these posts to build our list of alternatives and similar projects.

- With a bunch of projects in my mobile development career, mainly for startups, I can help you either with: - working on ongoing project: fixing bugs, implementing new features, propose solutions etc. create a new project from scratch, including: define business requirements, implement UI/UX per design, integrate required API, business logic, actively communicate with designers and backend.

- Refactor existing and build new Unity projects using the Zenject Framework

- Create loosly coupled connections using Zenject Signals

- Increate mobile game performance by using the Memory Pool classes provided by Zenject

- Create unit tests with Zenject and MOQ

Zenject Unity

- All prices of Course are in SGD.

- This Online Course is available in Udemy.

- Best $10 Offer on Dependency Injection in Unity3D using Zenject using Udemy Coupon. Discount was Updated on April 26, 2021 2:01 am.

The following article is a tutorial of sorts and will make the most sense if you follow along in Unity.

I recently started working on a new game in my own time. I won't talk much about it right now, as there isn't much to show yet, but I will soon.

For this game, I was determined to have some solidly tested code. In previous work places I've used Dependency Injection and am well aware of the power of Inversion of Control, not to mention the benefits it provides when writing unit tests. I've played with the Dependency Injection system Zenject before, but not on anything that went out at production level. Reading the docs, I was delighted to see that Zenject has added support for both Moq and UniRX since the last time I used it. This cemented for me that not only would I give Zenject a serious crack, but that I would also attempt to use Reactive Extensions (RX) in a game.

I won't go much into what RX is in this post. If you want to know more about it, I highly recommend you check out these videos from Infallible Code, they are excellent.

I also won't go too much into explaining Zenject and Dependency Injection. Again, check out Infallible Code.

Moq is a Mocking framework. It is extremely useful when writing tests, I couldn't imagine trying to write them without mocking.

Basically, I'm assuming if you have clicked on the link to read this blog, you have an idea on at least some of the things mentioned in the title. So let's get straight to the process.

Versions

I'm writing this blog using the following versions:

Unity - 2018.2.0f2

Zenject - 7.2.0

Moq - 4.7.99

UniRx - 6.2.1

Installation

Let's start with Zenject. Inside the Unity Editor, open the Asset Store window (Ctrl + 9) and search for Zenject. Select Download, and when that's done, Import. This will open an Editor Window showing all the files in the Zenject package with another Import button in the bottom right corner. Go ahead and click it.

You will now find a Plugins directory has been added to your project, inside of which is the Zenject directory. There's an Optional Extras directory and a Source directory. You now actually have everything you need to write unit tests with Zenject as the TestFramework classes are already in the Optional Extras directory. But we don't have Moq yet. If you navigate to Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/TestFramework/Editor you'll find a zip called AutoMocking.

Extract the contents of this zip directly into that Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/TestFramework/Editor directory. This will add some scripts and two more zips. Moq-Net35.zip and Moq-Net46.zip. You need to select one based on the Scripting Runtime Version you have selected in the Player Settings. Unzip Moq-Net35 (again, directly into the Editor directory) if you are using .NET 3.5 Equivalent

Or Moq-Net46 if you are using .NET 4.x Equivalent

I'm going to switch to .NET 4.x. If you also change your project, you'll notice the Editor needs to restart. Go ahead and do that. I'll wait here.

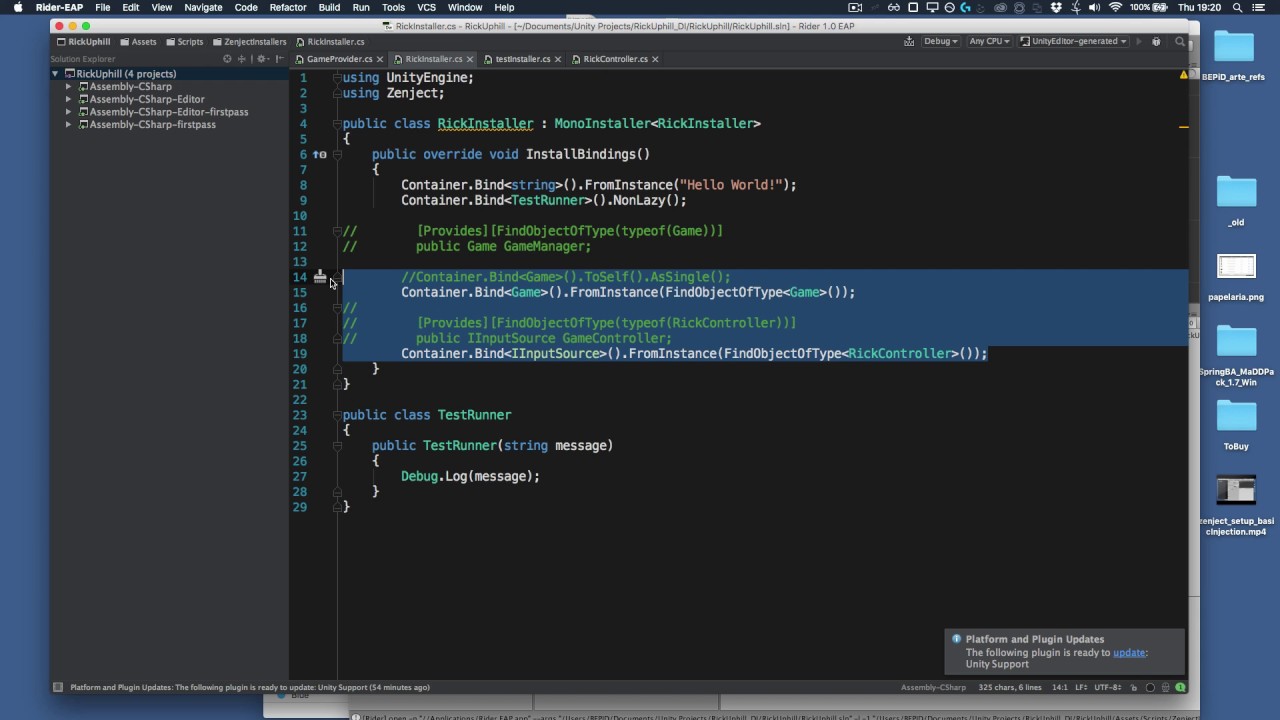

OK. If we open Visual Studio (Assets->Open C# Project) you may notice that the Solution Explorer shows many projects in your solution

This has to do with Unity adding support for Assembly Definition files. Zenject has been set up to use them also. So far, I've found them quite painful. I've had issues with trying to get project references to show up in the projects I need them in. So my solution for now is to kill all the asmdef files and go back to thye 'old way'. For Zenject, these are found in the following places:

- Plugins/Zenject/zenject.asmdef

- Plugins/Zenject/Source/Editor/Zenject-Editor.asmdef

- Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/TestFramework/Zenject-TestFramework.asmdef

- Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/TestFramework/Editor/Zenject-TestFramework-Editor.asmdef

- Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/MemoryPoolMonitor/Editor/Zenject-PoolMonitor-Editor.asmdef

Once you delete these files, your Solution Explorer will look like this

You will have some compile errors now though, as there are a couple of files in Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/TestFramework that need to be in an Editor directory for Unity to put them into the Assembly-CSharp-Editor-firstpass project that they need to be in to get a reference to the UnityEngine.TestTools and NUnit namespaces. This was being handled by the asmdef file before now. Simply locate the files

- SceneTestFixture.cs

- SceneTestFixtureSceneReference.cs

- ZenjectIntegrationTestFixture.cs

- ZenjectUnitTestFixture.cs

and drag them into the Editor directory that's sitting next to them

Now at this point, I've done this a few times, and each time I get a ton of compile errors in Unity, but not in Visual Studio. Simply shut down Unity and boot up your project again if you're seeing them too and they seem to magically disappear.

We now have Zenject and Moq installed and ready to write unit tests with. Let's quickly add in UniRX and we can start looking at some code.

To install it, simply search for it in the Asset Store and import like we did with Zenject. You will find that UniRX also has some asmdef files.

Plugins/UniRx/Scripts/UniRx.asmdef

Plugins/UniRx/Async/Unirx.Async.asmdef

Plugins/UniRx/Async/Editor/UniRx.Async.Editor.asmdef

Plugins/UniRx/Examples/UniRx.Examples.asmdef

If you remove these files you'll be back to the two projects in your solution. Keep in mind that these projects are basically Plugins and Plugins/Editor. Once we ad our own code we'll get two more projects. Essentially you can think of those two as Game and Editor.

As a quick explanation, anything in a directory called Editor in your project Unity bundles into a special project in the visual studio solution that has a reference to the UnityEditor assembly and isn't built into your game when you build. Plugins is another special directory that is separated out to minimise compile time, and any Editor directory in Plugins also gets it 's own project that is not built into your game. In this way, when you change any of your code and it has to be recompiled by Unity, it doesn't bother compiling the Plugins or Plugins/Editor code unless they also had code changes made. The use of Assembly Definitions to create more projects in the solution is an extension of this. You can limit parts of your code from having reference access to others as well as minimise recompile times by having smaller projects to compile. But so far I've found this more complication than it's worth.

Laying the foundation

Let's take this one step at a time. Let's set up some foundation code first, ready to test. Before that, let's get some folder structure in place. Create a new directory in Assets called Code. Inside that make one called Editor and in that, one called Tests.

We put the tests in an Editor directory so that Unity doesn't include them in our build. For this post we're only interested in writing Editor tests, not Playmode tests. This means we won't, at any point, run the game in the editor. We'll just run the tests from the Test Runner. We will also need a reference to the UnityEngine.TestTools and NUnit, neither of which are referenced by Unity in Assembly-CSharp I believe, so being in an Editor directory gives us this.

Inside the Code directory, create a new script. Let's call it MessageServiceManager. What we're going to do is emulate a central class that communicates with a third party messaging API of some sort. This won't be a MonoBehaviour, just a straight C# class. Let's pretend internally this class has an API and a Client that it needs to talk to that are a part of the third party message service we plan on using. For the sake of an interesting test, let us say the Client needs to be initialised with the API. So let's add a reference to an IMessageClient and IMessageAPI to our MessageServiceManager.

As expected, our solution has no idea what these two things are. We can create them from this file however, using Visual Studio's code generation.

Either right click on IMessageClient -> select Quick Actions and Refactoring ->Generate Interface 'IMessageClient' in new File

OR

with the caret on IMessageClient hold Ctrl and press . to bring up the quick actions menu and select Generate Interface 'IMessageClient' in new file

Do the same for IMessageAPI.

For now, we don't need code in there. We can generate that in a similar fashion as we write our MessageServiceManager class.

This MessageServiceManager is intended to be a singleton that can be injected into our other classes for handling messages. What those classes are aren't important, other than to think about how they might want to use this class. At the very least they will need a way to connect to something and a way to get messages. Let's add our connect method.

public void Connect(string Channel){}

Notice we take in a string for the channel we want to connect to. We'll assume for simplicity, that we're only able to connect to a single channel at a time. In reality, a use case for something like this might be one for each channel you want to connect to, and the class that uses these might collate all the messages from all the channels into a single UI feed. In that case you wouldn't make it a singleton and it's creation may come from a Zenject factory.

We almost have enough to write our first test. We're just missing one thing for our scenario. The dependency injection. We need a way to get the IMessageClient and IMessageAPI into this class. That's what Zenject does for us. We're using interfaces so that we can use Moq in our tests. We'll see why soon.

To set these up for Zenject to know they need to be injected, we simply use the [Inject] attribute above our two fields. This will again throw us an error as this class has no idea what the Inject attribute is. It's a part of the Zenject namespace.

To resolve this, we need to add the appropriate using statement, and the fastest way to do that is to again use the Visual Studio quick actions menu. With the caret on the Inject word, press Ctrl+. and select using Zenject. This will add the using statement to the top of the file and remove the red squiggly line.

It's worth noting at this point that we haven't actually wired Zenject or our Unity project/scene to know how to inject these, and we don't need to to write unit tests. We will set up something very similar in our test, but actually setting up Zenject in your scene is a topic for another day or Infallible Code's videos linked in the introduction.

That's our foundation complete. Let's write some tests.

First test

Now we need a test class. In Code/Editor/Tests add a new script called MessageServiceManagerTests.cs.

By now you'll see that we have the other two projects I mentioned earlier. The scripts we added in the Code directory caused Unity to create the Assembly-CSharp project and the test script we just created (which you'll notice is contained within a directory named Editor) caused the creation of Assembly-CSharp-Editor.

Open the test script. If you made it from within Unity, the class will inherit from MonoBehaviour, if you made it directly from Visual Studio, it won't inherit from anything. In Either case, we need to change it so that it inherits from ZenjectUnitTestFixture. Again, this will have the red squiggly and need the Zenject using statement added. If Unity made your script, remove the Start and Update methods also.

NUnit is the testing framework that Unity uses to run unit tests in the editor. It uses attributes to find classes that are test classes, and the methods within it that are tests to run. So we need to add the [TestFixture] attribute to the class itself to start with. This will need the NUnit.Framework using statement. We have now told NUnit that there is a class here that contains tests, and the test runner in Unity will go looking in here for some. But currently, it won't find anything, so let's add one that does nothing. For the test runner to recognise a method as a test, it must be decorated with the [Test] attribute.

I have a little personal rule when writing a test. I always try to write it in a way I expect to fail first and make sure it does. Early on in my learning for writing unit tests I had a few situations with false positives, usually to do with how the tests were written. So make sure you can make a test fail first. For our test case here we just want to see the flow into the Editor, so let's do the simplest of fails.

There is no way this test can pass. We're asking the test to only pass when the statement false is true.

Return to the Unity Editor now, and open the Test Runner. It's found in the Window menu. In Unity 2018, it's under the General sub menu. Dock this window somewhere. It should look something like this

You'll see that there are a couple of Zenject tests here also. These are only separated from yours because they are in a different assembly, the Plugins/Editor one. If they were in the same one as yours, they would be separated by Class name only.

You can optionally add a category name to the TestFixture attribute like this: [TestFixture(Category = 'MyTestCategory')]. This will allow you to filter the Test Runner window from the drop down to the right of the search bar. It should currently say 'nothing'.

You can either delete the file Plugins/Zenject/OptionalExtras/TestFramework/Editor/TestAutoMocking.cs to completely remove the tests, or collapse the Assembly-CSharp-Editor-firstpass.dll portion of the Test Runner.

Press 'Run All' in the top left to run all tests.

You can right click on any part of the tree structure in the Test Runner to just run the tests from there down.

You should find that the Zenject example tests pass (if you didn't delete them) and yours failed.

Before we celebrate, let's quickly change our test to pass in the most stupid way. Just to test our workflow is solid. Modify your test to Assert.IsTrue(true), come back to Unity, either 'Run All' or 'Rerun Failed' and watch everything turn green. The more you write tests, the more you'll grow to love all those green ticks. And curse those little red circles!

Great! Welcome to tested code!

Write a real test

So we have a test, but it doesn't really test anything. So let's write a real test. We want to test that when the MessageServiceManager has Connect() called on it, it calls Connect() on the IMessageAPI. So let's write a test for that.

There are a number of test naming conventions out there. Ultimately you can choose whatever you like, but personally, I like to just use the feature being tested with lowercase and underscores for readability and differentiation from non-test methods. I try to word it in a way that when read in the test runner, the green tick or red circle make sense.

The first thing we'll do is write out our test, even though the things we're referencing don't exist yet.

now at the top of the class, let's add a field for our MessageServiceManager called _testObject this is another naming convention I like. It makes it very clear in my tests what's being tested.

We also need to create a mock of our IMessageAPI interface. This is where Moq comes in. Moq essentially creates an inherited class, adding functionality to it that we can use. We can mock out method return values, verify methods are called (including things like verifying with certain arguments as we'll see and verifying a specific number of times). This is why we need to use interfaces. If we were using concrete classes, Moq could only create mock versions of things labelled as virtual. This isn't an issue when using interfaces. To create a mock, we simple declare a member of type Mock<T>. In our case

Mock<IMessageAPI> _mockApi;

This will require using Moq.

You may find that your class has an error under IMessageAPI. This is most likely due to Visual Studio generating the interface with the accessibility keyword internal which essentially means 'public inside this assembly' but it's not in the editor assembly that our test is. So change internal to public in IMessageAPI.cs

We now only have one error left. There should be a red squiggly under the Connect() in _mockApi.Verify(m => m.Connect());. If you hover over it, you'll see the error states something along the lines of IMessageAPI does not contain a definition for 'Connect' which is 100% correct. Our IMessageAPI class is an empty interface. Again, we can add this with the Quick Actions menu. Ctrl+. on it and select the top option, which should be Generate Method 'IMessageAPI.Connect'. Our error goes away, and if you press F12 on the Connect call, it will take you to the IMessageAPI file where you can see it.

So what does our test do exactly? It calls Connect on the concrete class that we're testing MessageServiceManager. Notice I'm passing in an empty string. That's fine, because we're not testing how we handle the channel variable yet. Then we are using a Moq method called Verify() on our Mock IMessageAPI. Verify will fail an Assertion if the method we call in the lambda argument hasn't been called. There are 12 overloads for Verify. But usually you'll just use this default one. The other common one includes a Times instance. This is a class in Moq used for defining various call count conditions. Such as Times.AtLeast(int count), Times.NoMoreThan(int count), Times.AtMost(int count), Times.Never(), Times.Exactly(int count_) and Times.Between(int min, int max, Range RangeKind). As you can see, this is quite flexible.

You may have noticed a couple of issues here.

1. _testObject and _mockApi are null

and

2. _mockApi isn't injected into _testObject in any way

The first one is easy enough to solve. At the top of our test we initialise them.

now Zenject. Hopefully you've either used Zenject before, or you watched the video linked at the start of this post and you understand that Zenject uses installers. An installer has a reference to a Container, and the Container is responsible for maintaining the bindings that are looked up for dependency injection. Containers and installers allow for different Contexts. Meaning bindings can be different in different situations, such as scenes. By inheriting from ZenjectUnitTestFixture we get access to a Container set up just for this class. In fact, you can look at the code for ZenjectUnitTestFixture. You'll see it's literally just new'ing up a DiContainer with a closed context. In this way we can feed it our mock versions to inject into the concrete class we're testing. This means that at run time, when we use the game installer which has bound concrete classes to IMessageAPI and IMessageClient, those will be injected instead. And since we tested our concrete MessageServiceManager's interaction with the IMessageAPI and IMessageClient, we can trust our class will behave exactly the same way in production as it did in our tests. Neat huh?

You may have notices another advantage here. Since we have no concrete class for IMessageAPI and IMessageClient yet, and in fact we have no content in those interfaces, we are building them from the tested functionality of MessageServiceManager. More than that, we are building the content of MessageServiceManager from the tests we write a little bit at a time. This is the basis of Test Driven Development or TDD. If you'd like ot know more about that, feel free to check out an article I wrote with Ash Davis on Testing for Game Development

One caveat to Dependency Injection is that you can't simply new up an object that has dependencies. You have to use the system to get new instances of the object so that it can fulfil the dependencies.

This means we need to remove the line where we new up the _testObject and instead put the [Inject] attribute on it. This way we are telling our DiContainer to inject it into this class. But if it's a dependency for this test class, how do we get the container to fulfil it? Luckily, we can do that with the following line Container.Inject(this);

This straight up tells the container that you have a reference to, in this case the one created in ZenjectUnitTestFixture, to fulfil any dependencies in the class passed in. Here that's this test class.

Perfect, but we're missing something. If we try to run this test it will fail. In the Test Runner, you can see the reason that the test failed. This is always good to look at. Sometimes the reason is something you didn't think of (another great advantage to testing, find the bugs before they're bugs). In this case, the fail message says 'Zenject.ZenjectException: Unable to resolve type 'MessageServiceManager' while building object with type 'MessageServiceManagerTest'

This is telling us that when trying to fullfil the dependencies of MessageServiceManagerTest it failed to resolve the [Inject] attribute on MessageServiceManager because it didn't know how to make one of those.

Fair call, our DiContainer is empty. We haven't bound anything to it. Pretty simple, let's add Container.Bind<MessageServiceManager>().AsSingle();

we could also call AsTransient() instead of AsSingle() and this would give a new instance each time a class requested it as a dependency. Make sure you put this before calling Inject()

Now our test still doesn't pass but our fail message has changed. Now Zenject is unable to resolve IMessageClient. If you look at our MessageServiceManager class, you'll see that the top most injected field is IMessageClient, so it's the first to fail. We can assume that once fixed, IMessageAPI will then fail, so let's just fix both now.

We need to add a Mock<IMessageClient> to our test, and then add them both to the DiContainer.

The binding we've used here says take an instance of a type and bind it to an interface such that any time a class asks for that interface to be injected, you provide it with this given instance. Specifically, we're saying when you Inject this class, and attempt to fulfil the dependencies of MessageServiceManager it's going to want an IMessageAPI. When it asks for that, give it _mockApi.Object. Object is a reference to the wrapped type. Since Mock<IMessageAPI> is obviously going to be of type Mock<IMessageAPI> while the MessageServiceManager needs an IMessageAPI object. The same for the binding on IMessageClient.

Let's run our test again. We have a new fail message. One that is closer to a real fail. Moq.MockException : Expected invocation on the mock at least once, but was never performed: m => m.Connect()

That's nice and readable. Calling Verify() tells the test runner that we expect the method Connect() to have been called on our mock api at least once, but it has not been called at all. Great! this is the meat of the test. This is what we want to ensure happens. So let's fix it.

Open MessageServiceManager and inside the Connect() method, add _api.Connect();

Save, jump back to Unity, rerun your tests and bask in the light of green ticks.

Testing method call with argument

OK, let's get cracking on our next test. Let's test that when we call Connect() on our MessageServiceManager we call Connect on our IMessageClient with the correct arguments.

Let's add a new test called calling_connect_calls_connect_on_client_with_api_and_channel. In my book, you can never be too verbose with test method names. You're never going to have to call them, so you don't have to worry about the awkwardness of typing that in code. You just have to worry about readibility in the test runner. Go ahead and make this method, don't forget the [Test] attribute. If you've thought ahead to writing the test, you'll quickly realise you need to set up all those bindings again. They only existed in the scope of the last test we wrote. We need everything to be fresh for this test. We could rewrite that at the start of each test. But we're programmers, we're better than that. So we could extract it all to a method, maybe called Init() or Initialise(). Let's do that. Extract out the initialisation code from calling_connect_calls_connecton_on_api() to a method called Init()

You can again use Visual Studio's Quick Actions menu. Highlight the code, Ctrl+. and select Extract Method

You'll now see an Init() method. And where the code was, is now a call to it.

But this still means we have to remember to call Init() at the start of each test. NUnit has thought of this for us, and can call an initialisation method before every test if there is one decorated with the [SetUp] attribute. So add that to Init() and remove the call from calling_connect_calls_connect_on_api()

IMPORTANT: there's a good chance the auto generated code made the method private. If that's the case, [SetUp] will not get called and in fact the test will not be run. The test runner will not give any log, warning or error about it. It will just show your tests as having not run. Make sure your [SetUp] method is public!

Now we don't need to call that every time. We can just write the meat of the next test. We want to verify that when Connect() is called on MessageServiceManager, Connect() is called on the IMessageClient with channelName and the API object that was injected, in this case our mock one. To do that, we define the variable in the .Verify() method called in the test.

Like before, with our IMessageAPI, we don't have a Connect method defined in our IMessageClient. Generate it like previously using the Quick Options. Make sure you switch over to IMessageClient and check what the auto generation created. Sometimes Visual Studio doesn't get it right. Especially with naming, so make sure your names are good argument names. @object is not great. Change it to api or something similar.

Now we can run our test and watch it fail.

So to pass the test we need to call Connect on our IMessageClient in our MessageServiceManager.Connect() method and pass in the right values. Pretty straight forward, below _api.Connect(); call _client.Connect(_api, channel);. Our test should now pass.

Verifying method call order

What if we need to be sure that Connect is called on the API before it's called on Client for whatever reason? We can test for that. This way, if another developer comes along one day, does some refactoring in this class, and without realising the implications, swaps the order of those calls, our test will immediately break and we'll know what caused the problem we're no doubt about to experience in our latest builds. There is a built in way to test if methods on a particular mock are called in a sequence. But not between two mocks. The easiest way I've found for this is to use the Callback() method and booleans.

In this test, we want a boolean to show that the api method has been called, and another to show that the client method was called after. This is the one we'll assert on. Callback() can be chained on the back of Setup() which is another Mock method we haven't used yet. It's more commonly used to define a known return value, but you can use Callback() to define an Action that will run after the method is called on a mock. You write it like this

mockObject.Setup(m => m.MethodToCall()).Callback(() => dosomething);

With fluent API's like Moq, I like to put each method on it's own line for readability. So we'll add a boolean apiConnectCalled and callOrderCorrect. Then we'll set up _mockApi to set apiConnectCalled to true when it's Connect() method is called.

Now we can mock out the mock client to do something similar, but it sets the value of callOrderCorrect to equal apiConnectCalled. This way, if IMessageClient.Connect() is called before IMessageAPI.Connect() then callOrderCorrect will be false. Another thing we can do when calling mock methods but don't care about the specifics of the arguments is use the It class. We can write It.IsAny<string>() and the mock method (Verify, SetUp or whatever) will not care what's passed into the mock. This saves making dummy values just to pass in.

Once our callbacks are setup, we can call _testObject.Connect() with an empty string and Assert that callOrderCorrect is true. Now, since we have already written the code in MessageServiceManager in this order, we would expect our test to pass. So let's try and keep to our rule of failing a test first, and quickly swap the order of the calls. Now when we run this test, we would expect it to fail.

Once you've verified that the test does indeed fail, swap them back and smile at the screenfull of green ticks. Maybe take a break, grab a coffee and just sit back and look at them for a while. A board full of passing tests is a bloody satisfying sight to behold.

Event testing

There are many more tests that a service like this would have. Like connection error handling. Let's add an OnConnectionError event to IMessageClient and test that our MessageServiceManager throws an exception. This isn't the best handling, but demonstrates a few more features nicely.

First, let's add the event to IMessageClient.

Notice that we had to add the System using statemnt.

This is a fairly short test to write. Let's call it exception_thrown_when_client_failed_connection_event_fired. The trick is we need to call some code that we know will throw an exception. Normally that would halt execution. NUnit allows us to wrap the code that we expect to throw in an Assert. Assert is generic and needs to be told what type of exception to expect. For simplicity, we will just use the basic Exception class, but you could write tests to ensure that specific exceptions are being thrown if you wanted to.

Assert.Throws<Exception>(() => {});

Now the code that we want to cause an exception is when the event on the mock is thrown. We can use the Raise() method to cause that. We don't need to worry about the sender or the EventArgs in this scenario, but again, you could mock out an event with specific args passed into it for testing how that's handled. Raise looks like this

_mockClient.Raise(m => m.OnConnectionFailedEvent += null, new EventArgs());

so our whole test is pretty simple looking.

When we run it, it should fail. The fail message says that the Assert expected a System.Exception but got null. This makes sense. We aren't even handling the event in our MessageServiceManager, let alone throwing anything yet.

So let's add a handler. Seems pretty simple, but we probably shouldn't do it in the Connect method. What if that method is called more than once? we'll end up leaking memory by adding listeners to the event over and over. We have two options here. The easiest one, is to add a new method to MessageServiceManager called Init and mark it with the [Inject] attribute in the same way we marked the field memebers we wanted injected. This is called method injection. Any arguments passed into this method will attempt to be filled out by Zenject and fail if it can't do it. More importantly, it happens after all other types of injection, and is perfect for initialisation logic. This is what we'll do. The other option would be to change the IMessageClient to be injected using constructor injection. In this case we would remove the [Inject] attribute from the field memeber, add a constructor that took an IMessageClient as an argument, and assign the passed in one to the field member. Like this

public void MessageServiceManager(IMessageClient client){ _client = client;}

Keep in mind, constructor injection isn't an option on MonoBehaviours as you can't access their constructors.

So let's add our initialisation method and subscribe to the event in there

At this point our test will still fail as we haven't thrown our exception yet. All we need to do is throw it in our event handler.

And now we have a green light.

RX Testing

Last test. I know this has been a long post, thanks for sticking with me. The one bit of tech I haven't touched on yet is RX. As I mentioned in the introduction, if you don't know what Reactive Extensions are, or specifically UniRX, check out Infallible Code's videos. We're going to look at a simple example. We're going to generate a stream of messages that are coming from an event in the Client.

First we'll write our test.

Let's walk through this. We are establishing a boolean to know if our stream has emmitted a value. We subscribe here in the test to the RX Observable called MessageReceivedObservable on our test object; the MessageServiceManager. Notice this doesn't exist yet. That's OK, we'll generate it shortly. We then mock out our mockClient to raise an event called OnMessageReceivedEvent (which doesn't exist) which uses a delegate that takes a child class of EventArgs called OnMessageReceivedArgs (which also doesn't exist).

So let's generate some code. First the event. Ctrl+. on the OnMessageReceivedEvent. You're only real option is to generate a property. This is the best VS can do when guessing what this is. Just accept that, and then F12 on it and we'll fix it. You'll see it's guessed you wanted an int property. Delete the int type, and the get and set and replace it with our event code like so.

Now let's generate our event args, again using Ctrl+. The top option should be to generate the class in a new file. If you want to take your tests further, you can flesh out this class to contain a message string and test the contents are propagated into the stream properly if you like. For the purpose of this post, I won't go any further than this basic test though.

We now need to generate our MessageReceivedObservable. Back in our test we'll use Ctrl+. on it and Generate Variable. You'll notice however that the best VS can do is give you an object property. So we'll redo this one too. The way I normally handle these types of RX streams, is to have a publicly exposed IObservable. This has a very limited amount of functionality. This way any external classes can basically just subscribe to it. Internally however, this will most likely be linked to a Subject.

Unity Zenject Instantiate

Change our object property to an IObservable<OnMessageReceivedArgs> property (which will require the System using statement). This is the object that external classes will use to subscribe to, to receive events as they are pushed into the stream. This is what we subscribe to in our test to set the boolean to true to know that our code is working. We don't want a setter on this, so let's remove that from here and flesh out the getter to return a variable called _messageReceivedSubject. Now we need to create this, so add private Subject<OnMessageReceivedArgs> _messageReceivedSubject;

Now we just need to hook up our subject to the event that comes from IMessageClient. Up till now our test should still have been failing nicely. Now this last step should flick it to a pass. First create and hook up the handler next to the one we made for handling the error message.

You can use a little code generation short cut by typeing _client.OnMessageReceivedEvent += and then pressing tab twice. This will auto create the handler method, with the correct arguments and put you in a position to type a new name if you don't like the one VS created for you. Once you're happy with the name, press enter. VS will automatically add a line in your new method throwing a not implemented exception so that if you do this and forget to fill out the method, your program will throw a clear error that that's the case. We'll replace that throw with our code, converting the event to a new event in our stream.

This is quite simple, we take our subject and call OnNext() on it, passing in the event args that IMessageClient just gave us. This is the main reason why I use the public IObservable abstraction in my classes. OnNext() doesn't exist in IObservable, so external classes can't mess with this stream in any way, that can literally just observe and react.

At this point you may notice a compile error that I missed. In our test class, we're being told that we 'cannot convert lambda expression to type 'IObservable<OnMessageReceivedArgs>' because it's not a delegate type'. This is because although IObservable exists in the System namespace, UniRX provides some handy extensions that allow us to use lambdas here. This error is solved by simply adding the using UniRX line to the top of our test class.

Now back in Unity our test should still be failing, but the error message should make it super clear why. We have a null reference exception. We've all seen them. In this case it's on the line in our test where we are trying to subscribe to our stream. I'll point out at this moment that you can debug your tests like any other code. Place a break point on that line, attach the debugger to unity and run the test. It will break and you can step through the code. If you do that, you'll reliase that our Subject_messageReceivedSubject is null. Fair call, we never initialised it. We can do that in the constructor or inline with it's declaration. That's a personal preference that is entirely up to you. But for this post I'll place it inline since we haven't needed to make a constructor for any other reason. So mine now looks like this

Return to Unity, run your test and you should see that beautiful green tick.

Conclusion

This post barely scratches the surface of unit testing, but it has hopefully given you the tools to create them in Unity using some great technology like UniRX and Zenject. I hope I've managed to display the power of unit testing as a development tool, especially when used to facilitate code design, and not just as an afterthought.

I've also attempted to display the power of mocking libraries like Moq and how they can be used with Dependency Injection to decouple your code and test it for peace of mind. There are many more unit tests a class like our MessageServiceManager would need to be covered completely, and there are also other forms of testing than unit testing, such as integration testing, UI testing and scene testing (a type of Unity specific integration runtime test) to name a few. Zenject has some ability to facilitate both integration and scene testing, and they have some documentation on that. UI testing is a trickier subject. There is a library I found recently designed for Unity, and I'll be experimenting with that on my game. So I suspect there'll be another post on here in the near future on that. Hopefully not as long as this one was.

I'll put up some links again, since you've managed to stick through this article.

For some insight on Zenject check out Infallible Code

For more information on UniRX, again, take a look at Infallible Code. He also has a Discord server, come and join me in there and try to convince him to continue the video series.

For more on testing for Game Development, you can attempt another massive article written by myself and Ash Davis from what-could-possibly-go-wrong.com

And to follow me in a more general sense, I hang out on a twitter a little

Zenject Without Unity

Feel free to comment if you have anything you'd like to add to the discussion or any questions on anything I've written here. I didn't touch on testing MonoBehaviours, so if that's something you'd like to see, let me know.

Unity3d Dependency Injection

Thank you for your time,

Adam